Original article from Cleveland.com

CLEVELAND, Ohio — Bryan Smith’s mother forced him into rehab at the age of 15 when she discovered that he smoked marijuana. That was not the drug that would put him on the path to heroin addiction.

That drug was a muscle relaxer prescribed to him that same year by his doctor to treat his back problems.

Now 32, Smith has been a heroin addict for nearly half his life.

It culminated Sept. 11 when he decided he was ready to die. He snorted and shot up enough heroin to kill himself. His mother found him unconscious on the living room floor of her Lyndhurst home. It took two shots of Naloxone to bring him back from the brink. Now, he says he wants to live, but it’s not going to be easy.

A cleveland.com reporter and videographer interviewed Smith numerous times this fall to gain a better understanding of what life is like in the grip of heroin addiction.

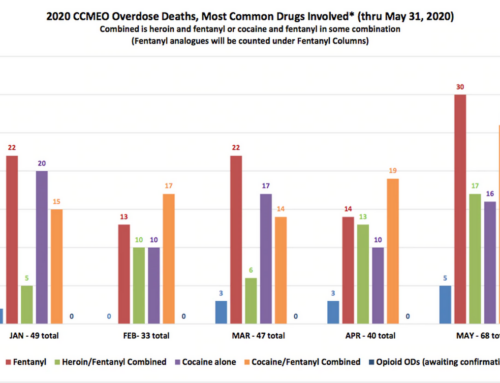

His fall into opioid abuse isn’t unique. It’s a story that’s told in homes and neighborhoods in every part of the United States, which finds itself in the throes of one of the worst heroin and opioid epidemics in modern history. Ohio has one of the highest death rates for opioid overdoses. In Cuyahoga County alone, well over 500 people are expected to die by the end of the year.

People young and old, white and black, rich and poor, and in urban and rural communities find themselves turning to heroin after spending months and years addicted to prescription painkillers.

What’s also not unique is Smith’s struggle with his addiction in a world of complex insurance regulations, relapses, long waiting lists at detox and rehabilitation centers and brushes with the law.

Path to addiction

Kathie Smith, Bryan Smith’s mother, said her son was a happy child. She has fond memories of him spending a whole summer wearing a bomber jacket, shorts and cowboy boots. At 14, he walked up and down Mayfield Road during spring break to get a head start finding a summer job, which he found at a local barbershop where he would eventually become the manager.

A year later, a doctor prescribed him Soma to help combat the pain associated with scoliosis. The prescription required him to take the pills “for pain, as needed,” but he soon started trading his pills for other drugs, like Vicodin.

“I would take them for pain, but I would also take them for fun too, you know?” he said.

He said he first used heroin at age 17.

He stepped up his drug use after the drowning deaths of his friends Chad Schreibman and Charlie Trizza on Mother’s Day 2002, as well as the unexpected death of his mentor, barbershop owner Mary Ellen Eues. Trauma is often a trigger for people already addicted to drugs to increase their abuse.

Smith dropped out of high school. He moved to Florida at age 20. He split his time between working at strip clubs in West Palm Beach and Miami. The state was once considered one of the easiest places for anyone looking to get their hands on prescription painkillers. In addition to the warm weather, Smith said he loved the ready access to pills and cocaine.

The government took notice of the doctor-shopping craze and law enforcement began to crack down on so-called pill mills. The crackdown had an unintended consequence. Many people who relied on an almost endless supply of painkillers prescribed by doctors turned to street dealers. Pills on the streets cost much more than the average prescription.

Smith — like so many others — also used cheaper heroin.

“You pretty much wake up, already sick, and if you have them, you’ve got a good day going,” he said. “If you don’t, you’ve got to go get them, sick, sweaty, puking, whatever.”

Smith kept his family in the dark about the depth of his addiction.

“We talked usually at least once a week, and if it got to be two weeks, then I’d start getting concerned, but it wasn’t like he wasn’t calling me or didn’t answer if I called,” his mother said.

He moved back to Cleveland at 28 when he decided to get clean. He entered rehab for the first time, but it wouldn’t be the last. His mother and sister say he can be stubborn, angry and combative, and they live in fear that they’ll never see him again.

Smith got sober for four months earlier this year and was admitted to the hospital for dehydration. He said a doctor placed him on fentanyl to relieve his pain. Cleveland.com requested Smith provide the hospital record from that day but Smith did not do so. It would be unusual for a doctor to give the opioid that’s stronger than heroin to someone with a history of drug abuse.

This relapse proved too much for him and he tried to kill himself.

Wanting to quit

Drug and alcohol abuse is difficult to overcome. Heroin is probably the hardest to quit.

The withdrawals are staggering, with vomiting, diarrhea, sleepless nights, pain and restlessness, in addition to the psychological effects the drug has on the user. Willpower and simply kicking the drug is often not enough. Users often need months or years of individual and group therapy to stay on the wagon.

Smith’s first interview with cleveland.com was Sept. 19, eight days after his failed attempt to kill himself. The late-afternoon sun, not an overbearing presence for most, was torture for him. Flop sweat poured from his forehead.

“Today has been kind of rough,” Smith said. “Probably the worst of it, I’d say.”

Studies say that without medication such as methadone or Suboxone, which are often prescribed to help curtail the pain heroin users experience during withdrawals, people who try to quit have a 90 percent chance of relapsing within the first three months of recovery.

During a recent trip to Columbus with his family, he took Suboxone. He wanted to stay alert during his visit with his father and his nieces. He admitted that he didn’t get his Suboxone from a doctor. He bought the medication from a drug dealer.

“To be 100 percent honest, I’m trying to create good memories right now because, God forbid something happens and I die, you know?” he said.

By Sept. 21, he was out of Suboxone and couldn’t find any more. He bought some heroin and relapsed.

“I wouldn’t even call it a relapse, really, because I’m still going through the detox process,” he said two days later.

A week later, his mother found another bag of his heroin, flushed it down the toilet and called the police. He ran away, and his brother-in-law picked him up and drove him to Elyria to stay at a cousin’s house. There, he tried to wean himself off the drugs.

“It’s kind of like when you’re in jail. It actually makes it a lot easier,” he said of staying in Lorain County. “I know it’s around here too, but I don’t know where to get it or nothing, so I don’t think about it like I do anywhere else.”

He said detoxing felt like going through a flu that wouldn’t go away. First he was hot. Then he was cold. He said he would feel jolts go through his legs and his body. He watched a lot of TV to try to keep his mind off the pain.

Getting into rehab

Early in his attempts to get clean, Smith tried to get into Stella Maris, a Cleveland-based detox facility. It was only after a week holed up in Elyria trying to kick the drug on his own that he heard from a Stella Maris official who told him he was admitted.

Smith admitted he did not check in with the facility to remain on the wait list, a requirement for those wanting to be admitted. But the wait reveals a problem for addicts.

Current federal laws don’t allow drug treatment centers with more than 16 beds to bill Medicaid, which limits the availability for many low-income drug addicts. Even for people like Smith, who has insurance, the wait can also be a long one.

Stella Maris nursing director Carole Negus said people can wait anywhere between four and six weeks before they’re admitted to the facility. That means someone motivated to quit may be told they’ll have to wait.

“If I could actually bring these people in when they were calling … I think that we would be getting them in what we call the ‘window of opportunity,’ when they’re ready to come in,” Negus said.

Smith entered Stella Maris on Tuesday, Oct. 11. He left a day later because he didn’t like the attitude of one of the counselor who was helping him develop his post-detox plans. Negus said Smith was dead-set on going to another facility, one that didn’t accept his insurance.

“His plan didn’t work out the way he wanted it to work out and so he didn’t want to listen to any alternative plan that his counselor gave him,” Negus said. “I believe in my heart a lot of times when we get that story and what the real story is that they just want to use.”

He doesn’t want to die

Smith’s mother and sister possess both hopefulness and skepticism about his claims that he wants to get sober. And the grim statistics about his chances of a successful recovery offer them little comfort and leave them feeling helpless as they try to save his life.

He was hospitalized Oct. 19 after he went into cardiac arrest as he went to a store with a friend to buy cigarettes. His sister, local activist Rachelle Smith, said doctors gave him Naloxone to revive him, but her brother insisted he wasn’t high.

He used heroin again the next day, and a drug test performed at the hospital confirmed that he was using.

When she learned that her brother used heroin, his sister told him that she wished he would just die already. She didn’t mean it, and she said she immediately regretted telling him that.

“I’m so tired of trying to figure out what’s true and what isn’t,” she said.

Even without heroin, his life is in disarray.

He is unemployed. He has an active warrant in Lyndhurst for missing a court date when he overdosed Sept. 11 in his attempt to take his own life.

Frustrated but concerned about his well-being, his mother let him move back into her house. She said while she can’t control his every move, she could, to some extent, help control his drug use. While the odds are not currently in his favor, his mother often still sees hints of the charismatic young man who charmed his way into a job at the age of 14.

“If he would ever get his act together, he could be a great businessman,” she said.

Smith said he’s determined to stay clean. He recently entered a rehab facility in Sheffield Lake.

“Why bother again?” he asked. “Because you never know when you’re going to get it.”