Northeast Ohio’s New Fentanyl Epidemic Hits Black Communities the Hardest:

While the opioid epidemic seems to have reached a plateau, that may just be masking a new problem. Three years ago, opioid deaths skyrocketed when dealers started cutting heroin with the often-lethal drug fentanyl. City, county, state and federal officials worked together that would develop solutions to stem the use of fentanyl. Just as they were beginning to see progress, the drug found a new form – being laced with cocaine instead. The results are equally deadly and have disproportionately affected black communities.

Below, Mike Tobin, Community and Public Affairs Specialist with the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Cleveland, Ohio, answers questions about the new epidemic – fentanyl-laced cocaine – and why it’s affecting some communities more than others.

- Is the opioid epidemic improving at all?

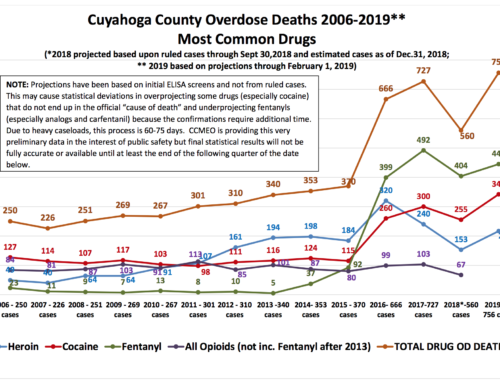

There has been progress but there are still massive challenges. While heroin overdose deaths are down 22% from the beginning of the epidemic in 2014, the streets have been flooded with fentanyl, which has caused an overall increase in drug overdose deaths. Just when we thought we had a handle on the opioid epidemic, here comes fentanyl again, this time mixed with cocaine. - How did the introduction of fentanyl change the opioid epidemic?

The data gives a pretty clear and unfortunate picture: Cuyahoga County saw 492 fentanyl overdose deaths in 2017. It killed an additional 217 people when combined with heroin. The pain relief narcotic turned street drug is an undetectable powder that’s often cut with other drugs, increasing the risk of addiction and death. People are buying drugs without a clue about what’s actually in that baggie. They think they’re buying heroin, but there’s fentanyl mixed in – and a tiny amount can be lethal. - What have officials done to deal with fentanyl-laced opioid use?

If there’s any good news in battling this epidemic, perhaps that’s the progress we’ve made by aggressively targeting fentanyl in street drugs. Cuyahoga County and the ADAMHS Board have provided funding for fentanyl test strips, and those are being distributed at needle exchanges and people are encouraged to test their heroin before using. This approach proved to be extremely effective, as fentanyl-laced heroin overdose deaths dropped from 63 in Q1 of 2017 to 37 in Q1 of 2018 (NOTE: This data might be a bit dated since we saw another surge in deaths in Q1 of 2019). There was a natural distribution channel for the strips that also allowed us to educate people on the dangers of using heroin in Cuyahoga County, because it’s no longer just heroin. - How has the drug epidemic changed recently?

We’ve seen a shift as people have become educated about fentanyl-laced heroin. Use has dropped, deaths have dropped and now we’re seeing other drugs being cut with fentanyl, especially cocaine. Six-hundred and sixty-seven Cuyahoga County residents died from cocaine-related overdoses between 2016 and 2018; 435 of those overdoses also included fentanyl and 235 of the victims were black. What that tells us is that we’re seeing a shift not only in the substance but also in the community it’s affecting: In the past, cocaine was a drug we saw more often in white communities. That’s no longer the case. - Why is this new epidemic affecting black communities more than other populations?

That’s a question we’re still trying to find the answer to. There are theories for why this is hitting black communities in such disproportionate numbers, but they’re only theories. Perhaps the simplest explanation is expanding the market – drug dealers needed a new customer base, and they found one in black communities. - What are the next steps in stemming this new drug epidemic?

I have heard from some quarters of the African-American community about concerns about how this epidemic is being handled, particularly compared to the way crack cocaine was handled in the 1980s and 1990s. I have been told on several occasions “when it was crack cocaine in the African-American community, the solution was to lock people up. Now that it’s white people dying, they need treatment.”Gaining the trust of Cuyahoga County’s black community to work together to spread the word on the dangers of fentanyl-laced cocaine is what we’re working on now. The message we’re trying to send in the black community, along with the greater Cleveland area as a whole, is that you truly do not know what’s in the drugs you’re using. Yes, drugs are illegal. But that doesn’t mean they should carry a death sentence. As government officials look for ways to tackle this new challenge, we hope our message remains clear – providing treatment and support for those who need it. We’re going to continue to do what works – sending drug dealers to jail while trying to get treatment for users struggling with addiction.