CLEVELAND, Ohio — Cleveland emergency room doctors saw a surge of patients suffering from suspected opioid overdoses in 2017, in a trend the Centers for Disease Control says suggests overdoses are on the rise in Ohio and in major metropolitan areas.

CLEVELAND, Ohio — Cleveland emergency room doctors saw a surge of patients suffering from suspected opioid overdoses in 2017, in a trend the Centers for Disease Control says suggests overdoses are on the rise in Ohio and in major metropolitan areas.

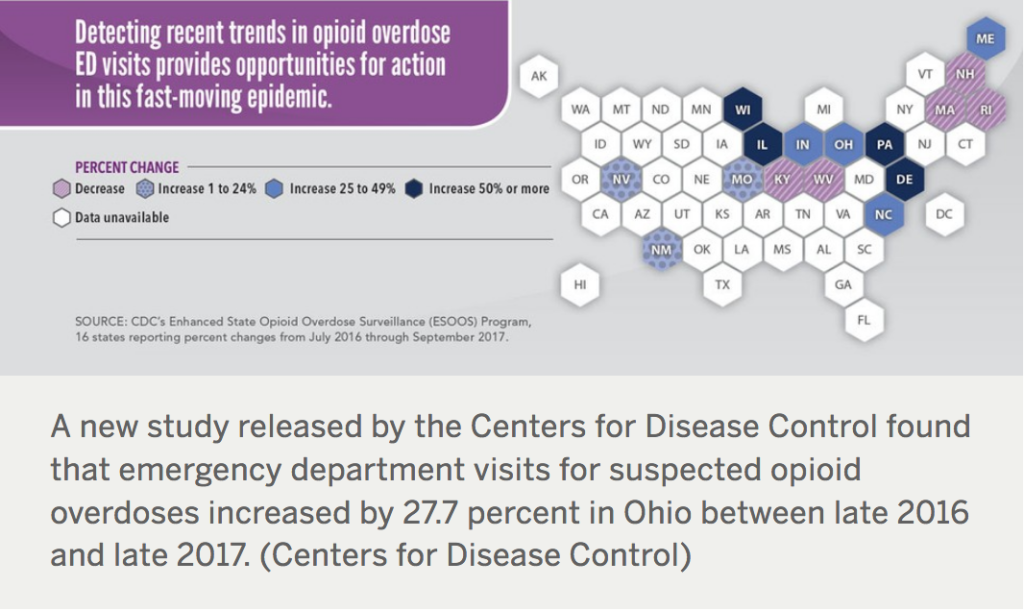

The CDC study released last week found that the number of Ohio emergency department visits for opioid overdoses increased by nearly 28 percent between July 2016 and September 2017. Large metropolitan areas across the nation saw an increase of about 54 percent in the same period.

The numbers suggest that the opioid epidemic is continuing to worsen across Ohio and in some Midwest states.

Dr. Mariam Diab, emergency room physician at St. Vincent Medical Charity Center in Cleveland, says that she noticed a marked increase in opioid overdose visits in her emergency room.

“The numbers are high and they definitely increased in 2017,” Diab said. “At times, we have at least seven or ten (overdoses) a day and sometimes that’s only what we (treat) that day.”

The CDC’s data shows that the largest overdose increases last year happened in Midwestern states and in large cities, which includes Cleveland. Like other major Rust Belt cities, Cleveland might be feeling the effects of this latest surge due to both its population density and location.

The country saw an overall 34.5 percent increase in opioid overdose emergency department visits last year.

Hospitals in some neighboring states saw much larger increases than Ohio and the nationwide average. Pennsylvania experienced a roughly 81 percent jump in that same one-year period, and Indiana logged a roughly 35 percent increase. Other Midwestern states saw a decline in emergency room visits — Kentucky had a 15 percent decrease and West Virginia had a 5 percent decrease, according to the study.

The executive director of the Kentucky Office of Drug Control Policy attributed the declines in his state to emergency responders increasing their use of naloxone, known as Narcan, which counteracts the effects of an opioid overdose, kentucky.com reports.

Ohio is one of 32 states that received funding over the past two years to participate in the CDC’s Enhanced State Opioid Overdose Surveillance Program, which provides researchers with more timely and well-rounded data about fatal and nonfatal opioid overdoses on a local level.

The program can track overdose outbreaks in near real-time and provides an avenue for quicker response compared to other cumbersome data collection methods like analyzing hospital billing data.

This new data can serve as an early warning system because “spikes in emergency department overdose trends…can potentially predict future fatal overdose trends and inform a more localized response,” according to the study.

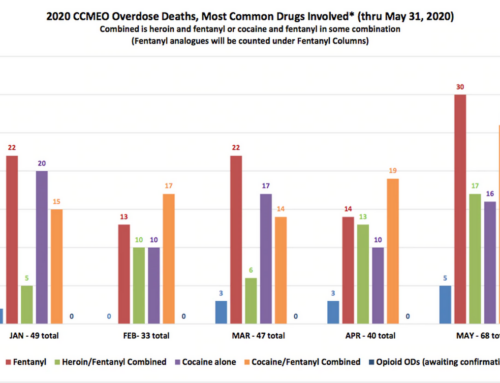

A comprehensive tally of fatal opioid overdoses in Cuyahoga County last year has yet to be finalized by the Cuyahoga County Medical Examiner’s Office, but preliminary numbers show that the death toll continued to sharply rise.

There were 353 drug overdose deaths in the county in 2014, 370 in 2015, and fatalities jumped to 666 in 2016. That number reached 822 in 2017, according to the most recent report released by the medical examiner’s office.

While the CDC did not release county-by-county numbers, Cuyahoga County’s continued increase in fatal overdoses is in line with the CDC’s data that suggest the opioid crisis in Ohio has not yet begun to plateau.

Dr. Baruch Fertel, director of quality for Cleveland Clinic’s emergency departments and a practicing emergency department physician, said his hospital “definitely saw a spike in overdoses in 2017.”

He emphasized that the opioid epidemic continues to be a major public health crisis, and one that has been aggravated by the climbing potency of street drugs that are often cut with powerful synthetic opioids like fentanyl and carfentanil.

Fentanyl, which is 30-to-50 times stronger than heroin, was identified in at least 477 fatal overdoses in Cuyahoga County in 2017, according to the medical examiner’s office. Carfentanil, which is 100 times more potent than fentanyl, was identified in about 192 overdose deaths — compared with 56 cases in 2016, and zero cases in 2015 and before.

“Anecdotally, patients have told me that it’s good for business if a dealer has a patient that overdoses, because it shows that they’re selling potent stuff. People want to be able to get high and they become more tolerant, (meaning) higher and higher doses are needed,” Fertel said.

The solution, Fertel said, must be a comprehensive one. Officials must address the needs of people already dependent on opioids, and seek to prevent a new generation of people becoming dependent on the drugs.

“We need to do whatever we can to get people treatment. We need to increase access to treatment centers, but make them affordable” for the underinsured and uninsured, Fertel said.

ORIGINAL ARTICLE: http://www.cleveland.com/metro/index.ssf/2018/03/cleveland_doctors_witnessed_sp.html#incart_m-rpt-1