When Covid-19 struck, the U.S. was already in the grip of an expanding drug-overdose crisis. It has only gotten worse since then.

Counties in states spanning the country, from Washington to Arizona and Florida, are reporting rising drug fatalities this year, according to data collected by The Wall Street Journal. This follows a likely record number of deadly overdoses in the U.S. last year, with more than 72,000 people killed, according to federal projections.

The pandemic has destabilized people trying to maintain sobriety or who are struggling with addiction during a time of increased social isolation and stress, according to treatment providers and public-health authorities. In a survey of U.S. adults released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 13% of respondents in June said they had started or increased substance use to deal with stress or emotions related to Covid-19.

Fatalities ClimbDrug deaths have risen in the past threedecades, in large part due to opioids.Number of drug deaths per yearSource: Centers for Disease Control and PreventionNote: Numbers for 2019 are provisional and includeprojections.

The drug deaths are adding to the pandemic’s toll, which includes more than 188,000 infection-related fatalities, but also other deaths linked to factors such as disruptions in health care and economic dislocation.

“It’s a pretty stark reality here,” said David Sternberg, clinical-services manager at the nonprofit group HIPS in Washington, D.C., which helps keep drug users safe and find treatment. “We’ve lost a lot of clients, a lot of patients.”

Moreover, social-distancing limitations are complicating treatment for people who struggle with addiction and for the organizations that provide services to them.

Benjamin Kief died of an opioid overdose on April 7 while in his car in West Chester, Pa. After serving time for a parole violation, the 30-year-old left a state prison in late March, when the pandemic was ramping up. He struggled to get an appointment with a recovery coach, said his mother, Mary Kief. He also wanted to start attending Narcotics Anonymous meetings, but they weren’t gathering in person due to stay-at-home orders and online video meetings made him anxious, she said.

“We had all these plans set up,” Ms. Kief said. But because of the pandemic, she said, “he didn’t have the resources.”

Drug-treatment providers say the federal government has helped amid the pandemic by loosening restrictions to make it easier to access addiction medication remotely, and are using telemedicine to reach people in need where possible. But people in recovery also often rely on in-person support services like group meetings, advocates say.

Ms. Kief planted a tree in her son’s memory in Newtown Square, Pa.

Photo: Hannah Yoon for The Wall Street Journal

The Journal, through data and public-records requests, asked the 50 largest counties by population for information on overdoses this year. Among the 30 that provided numbers, 21 of them showed overdose deaths trending up from last year. Among the other jurisdictions, several had only prepandemic data, and some said overdose tallies were flat or trending lower.

Federal overdose data has yet to catch up to the pandemic months.

Counties in Nevada, California, Ohio, Indiana, Minnesota and Michigan are among those showing increases. Authorities in other places, including traditional hot spots for opioid deaths like parts of Appalachia and New England, are also reporting more drug deaths.

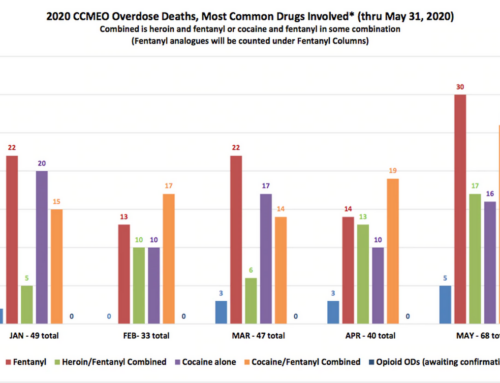

The spread of fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid, and increased use of methamphetamines were contributing to the worsening overdose problem before the pandemic. Many counties and states say the pandemic is amplifying the threat from these drugs.

SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS

How do you come to terms with the human cost of the coronavirus? Join the conversation below.

The Southern Nevada Health District, which covers Clark County, including Las Vegas, said fentanyl fueled an 8% increase in fatal drug overdoses for the first half of this year. Authorities in San Diego also said fentanyl is killing more people there.

In Los Angeles County, the nation’s most populous, overdoses rose 48% to 247 in the first month and a half of the pandemic compared with the same period a year earlier, said Gary Tsai, interim director of substance abuse prevention and control for the county’s public health department.

“They’re indoors, they’re stressed, maybe they lost a job or a family member,” Mr. Tsai said of the added stress factors some drug users face.

Shannon Hicks, who heads the harm-reduction group Exchange Union, distributed naloxone and sterile supplies in Martinsburg, W.Va., on Saturday.

Photo: Dee Dwyer for The Wall Street Journal

Early figures show that the overdose tally in Ohio’s Franklin County, which includes Columbus, reached 580 by late August, said county coroner Anahi Ortiz. That is near the entire total reported for 2019.

“I don’t think it would have been this high a number if Covid-19 hadn’t hit us,” Dr. Ortiz said. “We’re seeing a lot more relapses.”

Suspected overdoses rose almost 18% after stay-at-home orders were implemented across the country in mid-March, compared with the early 2020 period before the pandemic struck, according to data from the Overdose Detection Mapping ApplicationProgram, which collects real-time overdose numbers nationally.

Opioid users are typically advised against using drugs alone since that boosts the risk they could die without someone nearby to revive them with an overdose-reversal drug like naloxone.

Tanna Welch’s 35-year-old daughter, Holly Carver, died from a fentanyl overdose in late April while alone in her room at a group home outside Seattle, Ms. Welch said. The mother of three had completed a treatment program in February. But she had struggled with drug use for many years, in part to manage untreated mental illness, and the combination of her self-medicating, the dangers of fentanyl and the pandemic proved overwhelming.

“It was three converging storms, and it was just too much for her,” Ms. Welch said.

Holly Carver died in April from an overdose. Her mother blames it on the convergence of the pandemic, her self-medicating and the danger of fentanyl.

Photo: Tanna Welch

Shannon Hicks, who heads the West Virginia harm-reduction group Exchange Union, said she has seen a jump in overdoses.

“When Covid hit, nobody was allowed to touch anybody, nobody was allowed to see anybody,” Ms. Hicks said. “The worst thing for someone chaotically using drugs is to be isolated.”

The pandemic has also disrupted the supply of illegal drugs flowing up from the U.S.-Mexico border, possibly because restricted border traffic makes it harder for traffickers to move product inconspicuously, according to the Drug Enforcement Administration. These supply interruptions can heighten risks for users who seek new dealers and buy unfamiliar products.

“You can’t get the drug you’re used to getting, so you get your hands on whatever you can,” said Gavin Bart, who directs the addiction medicine division at Hennepin Healthcare, a safety-net hospital in Minneapolis.

The intensifying drug crisis is particularly crushing for advocates who celebrated a slight decline in drug deaths in 2018, which marked the first time in nearly three decades the U.S. death toll hadn’t risen. In the past decade alone, overdoses have killed more than a half-million Americans.

“I feel like all the work we did reducing overdoses just got tossed out the window,” said Jess Tilley, co-founder of the harm-reduction group HRH413 in western Massachusetts.

Write to Jon Kamp at [email protected] and Arian Campo-Flores at [email protected]

Copyright ©2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8

Appeared in the September 9, 2020, print edition as ‘Pandemic Worsens Nation’s Opioid Crisis.’