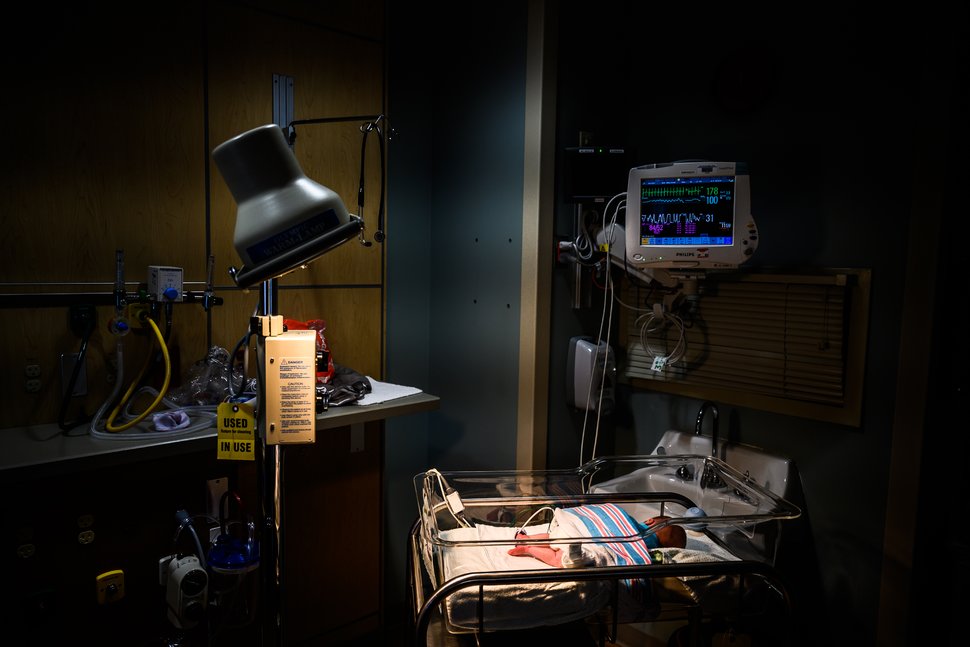

At least 2.2 million children had been affected by the U.S. opioid crisis by 2017, with that total poised to grow and the consequences likely to be felt for years to come, a new analysis shows.

At least 2.2 million children had been affected by the U.S. opioid crisis by 2017, with that total poised to grow and the consequences likely to be felt for years to come, a new analysis shows.

Parents’ opioid use is the primary reason children are affected by the crisis – whether they’re living with an addicted parent or have been removed from their home, or their parent is incarcerated or has died of an overdose – according to the report from the United Hospital Fund, a health policy nonprofit based in New York. Still, an estimated 170,000 kids had opioid use disorder themselves or had accidentally taken the drugs in recent years, the analysis says.

The children of the opioid crisis are likely to incur higher expenses than others during childhood – an estimated $117.5 billion in health care, special education and child welfare spending – along with another $62.1 billion in societal costs during adulthood, the study says.

Even assuming a continual downward trend in opioid use, the analysis says, there still could be 4.3 million children affected by the opioid crisis at a cost of $400 billion by 2030.

“Even if we could stop the epidemic cold in its tracks today, the ripples will last long into the future,” says Suzanne Brundage, the study’s lead author and director of UHF’s Children’s Health Initiative. And while states and the federal government have spent billions of dollars to combat the opioid crisis in recent years, its effects on children and families have been “overlooked in many places,” Brundage says.

Across the U.S. in 2017, the analysis says there were an estimated 28 opioid-affected children per 1,000, with state-level rates ranging from 54 in West Virginia to 20 in California. The total number of opioid-affected children was highest in California, at 196,000 in 2017.

These disparities reflect both the magnitude of addiction and the number of children living in a state, as well as local strategies to tackle addiction, Brundage says. For example, states where greater numbers of opioid-affected children enter foster care or live with other relatives – such as Texas and Florida – may have less robust or intentional programs aimed at keeping families intact.

Living with a parent dealing with drug addiction is considered an adverse childhood experience, or ACE. A recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that about 61% of adults have experienced at least one ACE, while nearly 1 in 6 reported four or more types.

Kids who experience a greater number of ACEs are more likely to become smokers and to be severely obese, suffer from depression and develop substance use issues of their own, according to the new analysis. On average, it says, children affected by substance use disorders experience 2.1 ACEs in their lifetimes – a significant but not “abnormally high” number, according to Brundage.

“Clearly, the opioid epidemic is a generator of ACEs,” Brundage says. “ACEs are a normal part of our society, unfortunately, and what we need to do is think about ways of preventing ACEs and building resilient families.”

Last year, President Donald Trump signed the Family First Prevention Services Act, which seeks to keep children with their parents and relatives rather than placing them in foster homes. The law enables states to use federal foster care and adoption assistance funding for mental health, substance abuse and parenting skills programs for parents at risk of losing their children. It’s still unclear how the law will be implemented, though, as many states have delayed doing so.

“The opioid epidemic is clearly driving forward a wave of children affected by family substance use disorder,” Brundage says. “We need policymakers, (the) private sector, community leaders and the general public to … start responding today.”

ORIGINAL ARTICLE: https://www.usnews.com/news/healthiest-communities/articles/2019-11-13/the-opioid-crisis-has-affected-more-than-2-million-children?src=usn_fb&fbclid=IwAR385FvAj55mx-I9OWOR87dCbHNEJV_FDm38Pi-QJo-1SyRW1EkoV5jjt7w