Original article and images from www.cnbc.com.

Taylor Kay was driving on Interstate 290, heading east near Chicago, when a car veered across lanes of traffic into the highway median.

“I thought, ‘Something is wrong,'” the 26-year-old said. “So I get out of my car, and I see he’s overdosing, with a needle still in his arm.”

Kay recognized what was happening to the driver because it could have happened to her. She had used heroin for six years, until she was 24, and she herself has overdosed. She knew what to do.

“I go to my car and I get my Narcan, because I always have it with me,” Kay said, referring to the brand name of the drug naloxone, which quickly reverses opioid overdoses. “Once I put the Narcan in him, it took about 20 seconds. … I was so scared that this kid was going to die.”

He didn’t; he woke up, Kay said. She called 911, and the paramedics who arrived later told her the driver had taken fentanyl — a synthetic opioid up to 100 times more potent than morphine.

“Any longer,” Kay said, “he would have died.”

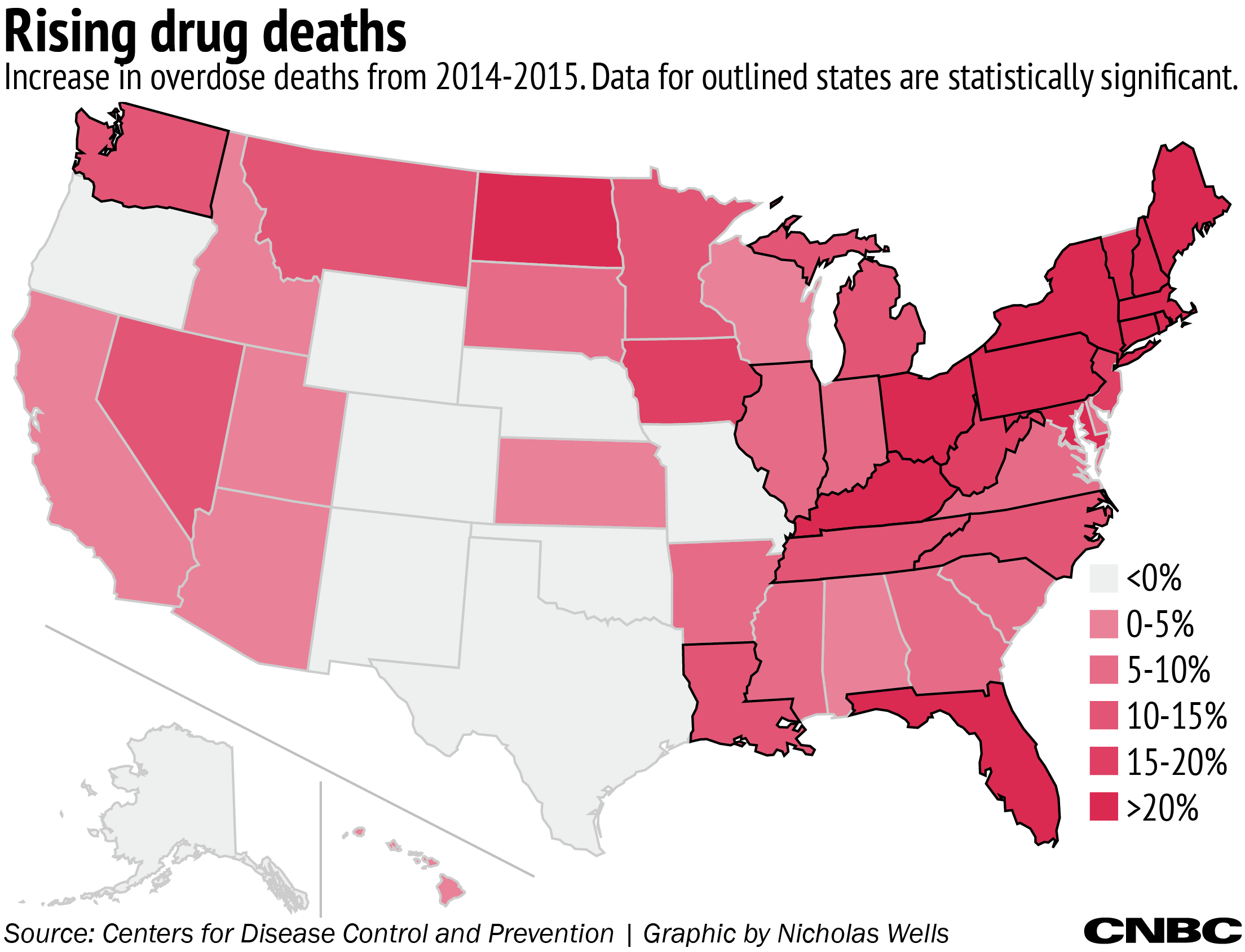

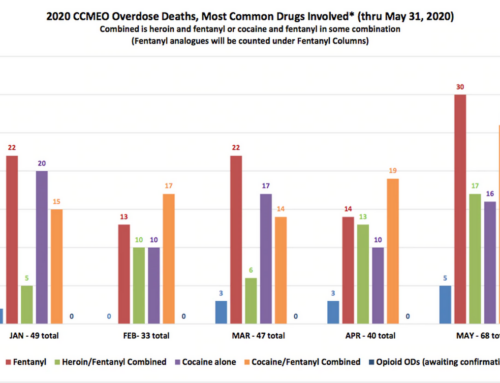

It’s an epidemic playing out across America as prescription painkillers lead to addiction, and their price on the street often causes people to turn to heroin. In 2015, for the first time, the number of deaths from heroin overdoses in the U.S. surpassed those from gun homicides, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In total, more than 33,000 people in the U.S. died from opioid overdoses.

As the number of opioid overdoses has skyrocketed in the U.S., so has the price of the drug that can wake someone up from a situation like Kay described. And in some cases, the rising prices make it hard for first responders and others to carry naloxone, which public health experts say threatens their ability to save lives.

“I’ve seen the price of Narcan as well as epinephrine just skyrocket,” said Brandon Heard, a fire department captain in Farmington, New Mexico. While he referred to the brand name Narcan, Farmington Fire uses a generic form of the medicine. “It makes it difficult for us as a municipality to purchase the same medications and provide the same treatment and abilities that we have in years past.”

Farmington Fire is switching away from the EpiPen, the lifesaving auto-injector for allergy attacks, in favor of vials of generic epinephrine and syringes, in order to save money. The department already uses a makeshift system for naloxone, with a preloaded syringe and a nasal spray attachment.

Public health experts say having naloxone in the hands of first responders — from firefighters to police officers — is vital; it can provide precious minutes before more medical help can arrive.

The antidote

When someone takes too much of an opioid drug like heroin or prescription painkillers, which bind to opioid receptors in the brain, it can cause the body to stop breathing. Naloxone acts as an opioid antagonist, knocking opioids off those receptors in the brain and restoring breathing. Administration can bring someone back in seconds.

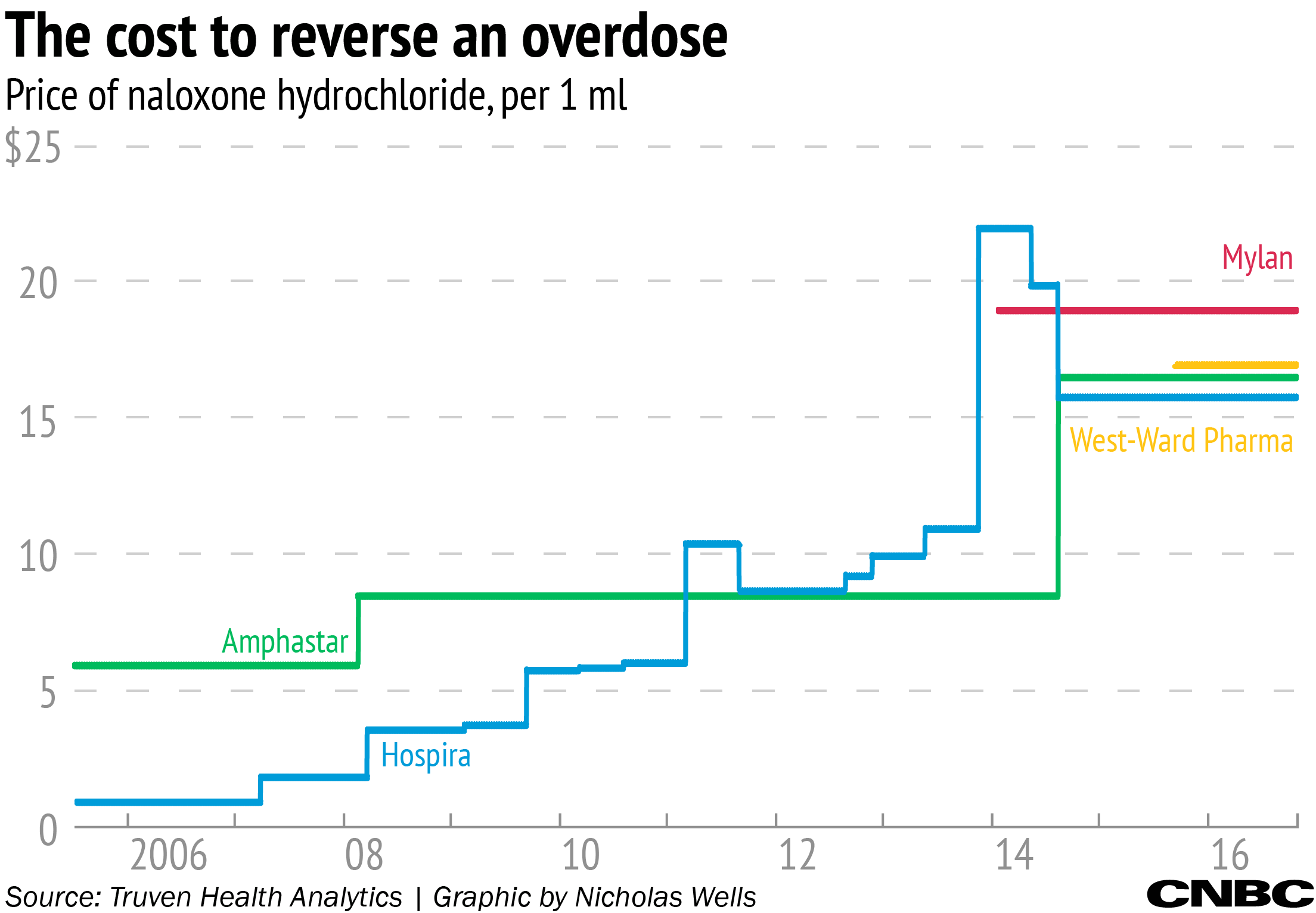

Naloxone has been available since 1971, originally under the brand name Narcan, and now in several generic forms, as well as formulations with new delivery systems. Both categories have their own cost stories; a generic form made by Hospira, now owned by Pfizer, rose in price from less than $1 per milliliter vial in 2005 to more than $15 in 2014. The newer delivery systems range in price from $125 for two doses to as much as $3,750.

It’s a pricing story not unique to naloxone. Prices have risen for certain generic drugs across the pharmaceutical industry, most recently garnering headlines with EpiPen, which is owned by Mylan. In many ways, aspects of the naloxone story are similar: While the prices of some older generic drugs rise, new delivery systems carry higher and higher price tags.

Cost of convenience

Taylor Kay was carrying the Evzio auto-injector that day on the highway. Made by Richmond, Virginia-based drug developer Kaleo Pharma, the device is about the size of a deck of cards, and actually talks to users while they administer it.

“I love that it talks to you,” Kay said. “With the syringe, it’s like: You have to go get the syringe, get the vial, and put the medicine in … with the auto-injector, you just take the cap off, and it speaks to you, and then it talks you through how to use it. So it is a lot faster.”

The Evzio has a list price of $3,750 for two auto-injectors, up more than 550 percent since it was introduced in 2014, according to data from Truven Health Analytics.

“We call it the Courvoisier of the overdose injector,” said Dan Bigg, director of the Chicago Recovery Alliance, a group that works with the drug-using community to distribute naloxone, among other services. Kay works with CRA, which received a charitable donation of the auto-injectors from Kaleo.

But some question whether the high price is justified by the new delivery system.

“We have all kinds of pretty amazing children’s toys that talk to us, too, which are pretty inexpensive,” said Dr. Eric Ketcham, medical director of the emergency department at San Juan Regional Medical Center in Farmington, New Mexico. Ketcham testified in front of Congress in September about the price of both naloxone and buprenorphine, a medicine to treat opioid addiction.

The Evzio is one of two naloxone products approved in recent years focused on use in the community, not in medical settings. The other is a nasal spray made by Adapt Pharma, the only naloxone product that actually still bears the Narcan brand. That medicine has a list price — before any discounts — of $125 for two doses.

Adapt says it hasn’t raised the price of Narcan nasal spray since it was approved in 2015, and that it provides steep discounts to $75 for a carton of two devices for first responders, community organizations, law enforcement and other public agencies. And it says for patients picking up the drug at the pharmacy, a majority has insurance coverage and pay a co-pay of $10 or less.

But some, like Ketcham, still see the cost as prohibitive, and — similarly to the Evzio — not justified by the changes in delivery system.

“The squirt bottle is pretty simple technology,” he told CNBC. And while Ketcham took issue with Adapt’s pricing, in his congressional testimony he called the Evzio’s price “truly astounding,” a sentiment echoed by others.

It’s “not only the big percentage increase that we’ve seen in the price, but also the amount of dollars involved,” said Michael Rea, founder and CEO of Rx Savings Solutions, which offers a software to help make decisions about prescription drugs, including based on their cost. “That gets your attention.”

Spencer Williamson, Kaleo’s chief executive, says it’s not that simple.

“The list price, which gets a lot of media attention, is a price that really nobody pays,” Williamson told CNBC in a telephone interview. “What we focus on is what a patient pays.”

Williamson was referring to what the patient pays at the pharmacy, the co-pay. He said Kaleo has a financial assistance program to cover the co-pay for any patient with commercial insurance who has trouble affording it — a program the company put in place after a patient who was prescribed the Evzio died because she didn’t fill her prescription, he said.

“Unfortunately, in that first year, about 75 percent of the time the physician wrote a prescription, the patient never got the product,” Williamson said.

In order to increase patient assistance, he said, Kaleo raised the Evzio’s list price. The company also will cover the whole cost of the drug if a patient has trouble with insurance coverage.

“When you net all that out, it’s a business model that works,” Williamson said. “But it’s primarily focused on ensuring the patient is not paying out of pocket to access this lifesaving therapy.”

Kaleo has also donated more than 150,000 auto-injectors to first responders, public health departments and not-for-profit community groups across 34 states, Williamson said. He noted more than 2,400 lives have been saved with the Evzio since it was introduced.

“We’re proud of our access and affordability,” he said.

The model of raising a product’s list price while making it cost less to patients at the pharmacy is an example of the complicated calculus governing how we pay for drugs in this country, said Ronny Gal, a biopharmaceuticals analyst at Bernstein.

Because of differences in insurance coverage, some patients are exposed to greater portions of the cost of their medicines, and those patients feel price increases more acutely. The outcry over the EpiPen’s rising price, for example, was primarily from a segment of patients without insurance or with high-deductible plans, who saw their own costs going up at the pharmacy counter, he said.

“In order to be able to raise your price on an entire population 20 to 30 percent, you want to make sure that the population who cannot pay for this is insulated,” Gal told CNBC. The drug industry, he said, “is finding channels to pay for people who cannot afford it so they can raise prices on the people who can.”

Covering patients’ co-pays or giving away medicines for free, he said, are some of those channels. Ultimately though, the rising prices affect everyone.

“At the end of the day, somebody’s always paying for it,” Rea said. “The chances are good it’s you and me, either via tax money or via our health insurance premiums.”

Competition’s false promise

Dr. Leana Wen, health commissioner for Baltimore, declared opioid overdose a public health emergency in 2015. And she says access to naloxone is a key part of making a difference in the epidemic.

“I’ve seen how it saves someone’s life within seconds,” Wen told CNBC. She has issued a blanket prescription for naloxone to every person in Baltimore. “Everyone should have naloxone in their first-aid kit. Everyone should carry it in their purse, their bag, their worksites. Because if we can save someone’s life in a couple seconds, it’s our obligation and our duty to do so.”

But, Wen said, the price of the drug can be a problem.

“The price of naloxone has escalated in our city, just like in other cities across the country,” she said, “which is limiting our ability to save lives.”

Wen takes particular issue with the price of generic forms of the medicine, which have risen despite competition.

There are now at least four manufacturers of generic naloxone in the U.S., and each product is priced similarly. It’s a picture that runs contrary to the argument that competition should bring prices down.

The generic naloxone made by Hospira cost $9.20 for 10 1-milliliter vials in 2005, according to data from Truven. By July 2013, that price was $109.90. Six months later, Hospira doubled the price, to $219.90, or about $21.90 per milliliter, before settling at $158.30.

Later in 2014, a competitor’s price followed a similar pattern: Amphastar’s naloxone jumped from $169.50 for 10 2-milliliter vials to $330, or about $16.50 per milliliter — a near doubling in price a few months after Hospira’s. Two other manufacturers sell generic naloxone at similar prices: Mylan, at just under $19 per milliliter, and West-Ward Pharmaceutical, at $17.

“From the perspective of a producer, if you come into the market and you can get a fair share without bringing your price down, you would,” said Gal, the Bernstein analyst. “The reason you raise prices is because you can.”

The increases have caught Congress’ attention. In September, the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Regulatory Reform, Commercial and Antitrust Law held the hearing on naloxone and buprenorphine pricing where Ketcham testified.

The congressman representing much of Baltimore, Rep. Elijah Cummings, along with fellow Democrat, Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont, wrote a letter to Amphastar in 2015 asking about the price increases for its product.

And most recently, the Senate Aging Committee’s Sens. Claire McCaskill, D.-Mo., and Susan Collins, R-Maine, wrote to five manufacturers about the prices of naloxone products. In late November, they wrote a follow-up letter to Pfizer, which bought Hospira in 2015, requesting information about how Hospira decided to raise prices, whether the increases support research to improve naloxone, and whether any access issues arose as a result.

“From the time naloxone entered our portfolio in September 2015, our focus has been on providing access to this life-saving treatment,” Pfizer said in a statement. “We believe it is priced responsibly.”

Additionally, the company pointed out, the list price doesn’t reflect discounts offered to customers, and said its generic naloxone isn’t like other branded versions typically used by first responders. Pfizer also has a naloxone access program that provides donations of up to a million doses over four years, as well as a $1 million grant to five states to support awareness of risks of opioid addiction.

Amphastar, whose generic product is often used by first responders as part of a kit with a nasal attachment, emphasized its last price change was in October 2014. The company said it was the result of business dynamics, including manufacturing of all of its drugs in California, where costs have been rising for materials and labor; investment of millions of dollars in research and development to bring an approved intranasal naloxone product to market; and spending $11 million to modernize and increase capacity of its factory that makes naloxone.

“When considering any price change, Amphastar always strives to meet the goal of providing safe and effective drug products at an affordable price,” Amphastar President Jason Shandell said in a statement.

The company also has rebate agreements with 11 states to equip first responders with naloxone, and says it will offer similar agreements to all states that want to improve access.

Despite charitable donations from multiple companies, public health experts still say cost is a problem.

“We are grateful for those donations,” Wen told CNBC. “But we should not be dependent on the goodwill of these companies in order to deliver a lifesaving medication.”

Naloxone is only one part of the solution to the opioid crisis, public health experts stress. It’s the acute solution to keeping someone alive, not the treatment for addiction — a system that they say requires much more attention and funding to make a dent in the opioid epidemic. But making sure patients have that chance for treatment, they say, is critical.

“We have to save someone’s life right now,” Wen said. “Because if we don’t save their life today, there is no chance for a better tomorrow.”