CLEVELAND, Ohio — Margaret Temponeras started her medical career in a small town as a family doctor. She ended it a felon, a rogue physician who authorities say fanned Ohio’s opioid epidemic with a prescription pad.

CLEVELAND, Ohio — Margaret Temponeras started her medical career in a small town as a family doctor. She ended it a felon, a rogue physician who authorities say fanned Ohio’s opioid epidemic with a prescription pad.

From 2006 through 2012, Temponeras ordered more than 1.6 million pills of hydrocodone and oxycodone from her offices in the tiny town of Wheelersburg, along the banks of the Ohio River.

That was more than any other medical practitioner in the state and more than some pharmacies. The drug distributor that supplied her kept shipping pills, despite her ever-increasing orders.

Eight of her patients died in her care, federal records allege. One was Ira Marsh, a 38-year-old laborer, who saw her over a three-year period during which she treated him for a back issue. Then, on Oct. 28, 2009, Temponeras prescribed him the opioid oxycodone, the muscle relaxer carisoprodol and the anti-anxiety drug Xanax, according to federal court filings.

He was found dead the next day.

“It’s unfathomable to me,’’ said Haley Burchett Grooms, Marsh’s sister. “I would ask him, ‘Where are you getting all those pills? No normal doctor prescribes that many pills.’ ’’

In 2013, the state revoked Temponeras’ medical license, two years after a crackdown of “pill mills’’ across Ohio. Addicted patients with no reliable source of prescription opioids fled to cheaper, more dangerous drugs.

“Oh God, we saw a massive transition from pills to heroin and fentanyl,’’ said Lisa Roberts, a nurse with the Portsmouth Health Department in Scioto County. “The pharmaceutical companies and the doctors frontloaded the problems that we have now.

“They were the jet fuel that kicked this all off. The heroin dealers already had a willing and able market.’’

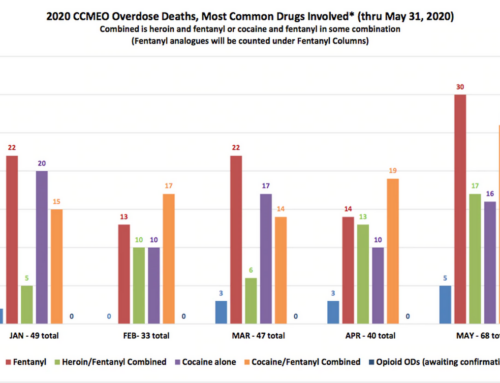

From 2010 to 2018, Ohio’s rate of accidental opioid overdoses per 100,000 people rose from 9 to 27, according to preliminary figures from the Ohio Department of Health. Cuyahoga’s rate tripled from 10 to 31. In Scioto County, where Temponeras practiced, it ballooned from 11 to 54.

From her pain clinic in Wheelersburg, surrounded by a handful of other clinics, Temponeras was in the middle of the opioid epidemic, and authorities said she helped fuel it.

“What she did is beyond comprehension,” said Orman Hall, the former director of the Ohio Department of Alcohol and Drug Addiction Services.

In 2017, she pleaded guilty to a charge of drug conspiracy in U.S. District Court in Cincinnati involving her prescribing of oxycodone, diazepam (Valium) and alprazolam (Xanax). She is expected to serve as much as seven years in prison, though a date for her sentencing has not been set.

Her attorney, Brad Barbin, said Temponeras was misled by the pharmaceutical firms. He said there were no guidelines or standards for prescribing opioids in Ohio, or nationally.

But State Medical Board records say Temponeras’ prescribing of painkillers was “for other than a legitimate medical purpose or outside the usual scope of professional practice.” The records also state that she continued to prescribe pills for patients who showed clear signs of addiction.

Temponeras, however, was a cog in a much larger distribution network.

In October, Cuyahoga and Summit counties are scheduled to go to trial in U.S. District Court in Cleveland over lawsuits against pharmaceutical companies that they say contributed to the crisis. About 2,000 local and state governments have sued the companies, claiming the businesses blanketed the country with painkillers in search of profits.

Earlier this month, two smaller manufacturers, Endo International and Allergan, agreed to pay a combined $15 million to settle their lawsuits with Cuyahoga and Summit counties.

Pharmaceutical companies distributed about 3.4 billion opioid pills in Ohio from 2006 through 2012. The state ranked fourth nationally, behind California, Florida and Texas, according to a Plain Dealer analysis of a U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration database released in July. The database tracked the sales and shipments of oxycodone and hydrocodone to pharmacies and doctors.

It also provided a window into Temponeras’ business.

A thriving practice

Temponeras, 54, started her medical career in the typical fashion: She earned her degree from the Medical College of Ohio in Toledo in 1992 and her state medical license five years later.

She went to work in Wheelersburg, just miles from the offices of her father, John, a well-known local gynecologist, who is now 84. She practiced family medicine, spent time with her parents and raised a son.

In 2005, she opened Unique Pain Management on Center Street in Wheelersburg and began treating patients for pain. At the time, the state did not require specific licensing of pain-management doctors or their clinics.

There, federal prosecutors said in documents, Temponeras saw about 20 or more patients a day from Ohio, Kentucky and West Virginia, charging $200 to $225, in cash, each visit. Some drove as many as 100 miles to get to her clinic, State Medical Board records say.

New patients also paid a $40 application fee and $90 for a urine screening, the results of which were often ignored, according to the federal indictment in her case. Her father filled in for her when she was away, and he wrote hundreds of prescriptions for her patients, State Medical Board records say.

It soon became clear that large numbers of the clinic’s patients were addicted to oxycodone or hydrocodone, the indictment said. Some crushed the pills and snorted them, while others dissolved the pills in water and placed them in a syringe to inject, according to interviews and State Medical Board records.

“Many of your patients have exhibited needle track marks, according to a physician in a hospital emergency room who has seen your patients,’’ a note in a State Medical Board report said.

Despite that, her practice appeared to grow.

The Plain Dealer’s analysis found that Temponeras ordered 107,300 pills of oxycodone and hydrocodone in 2008. The next year, she purchased 655,300 pills. The number of pills peaked in 2010, at 828,310.

She frequently prescribed what some locals called “the Holy Trinity,” or the “Scioto County Cocktail”: a mix of opioids, muscle relaxers and anti-anxiety medication, according to interviews, Temponeras’ plea agreement and court documents.

“I called it a recipe for an overdose,’’ said Roberts, the nurse for the Portsmouth Health Department.

Initially, Temponeras steered many of her patients to Medi-Mart Pharmacy in Portsmouth, a business owned by Raymond Fankell, who worked closely with her, federal prosecutors said in documents. Her business slowed, however, when Fankell and other local pharmacies began refusing to fill her prescriptions.

The reason stemmed from DEA officials warning local pharmacists about Temponeras’ excessive prescribing, according to interviews and court records.

To solve the problem, Temponeras started filling prescriptions from her clinic in 2008. She offered a one-stop shop, as she wrote prescriptions in one office and had employees fill them in another.

The employees, however, were not pharmacists and had little experience in health care, records show. At the time, state law did not require the Ohio Board of Pharmacy to license the office of a solo practitioner who dispensed drugs.

“Employees have unfettered, unsupervised access to the drug stock,” state investigators wrote in a report on the clinic. “Additionally, the facility does not maintain adequate records of the receipt and sale of dangerous drugs.’’

In a span of less than four years, Temponeras ordered 1.66 million pain pills. The Plain Dealer found that she ranked 18th out of the 64,252 practitioners nationwide who ordered opioids from 2006 through 2012.

‘Orders should never have been shipped’

From November 2008 to August 2010, Temponeras obtained more than 1.4 million oxycodone and hydrocodone pills from Miami-Luken, a pharmaceutical wholesale distributor in Springboro in Southwest Ohio, according to The Plain Dealer’s analysis. Distributors obtain and ship drug manufacturers’ products to medical facilities and, in a few cases, doctors.

In May 2018, Dr. Joseph Mastandrea, the chairman of the board of Miami-Luken, testified before a U.S. House subcommittee about the opioid epidemic. He said the board did not realize the distribution practices being employed by the company’s top executives until 2013.

In response to questions from the subcommittee, Mastandrea specifically mentioned Temponeras and the large amount of pills she had received. Even though it was legal for Miami-Luken to send shipments to her directly, he maintained that the company should not have done so.

“We never should have supplied to a dispensing physician,” Mastandrea testified. “Those orders should have never been shipped.”

In discussing the lack of follow-up, Mastandrea admitted that the company’s top executives once drove to Wheelersburg to check on Temponeras’ clinic. When it was closed for the day, they left.

They never returned.

In July, a federal grand jury in Cincinnati indicted Miami-Luken on drug conspiracy charges. The indictment accused the company and top executives of selling millions of opioid pills in southern Ohio, Kentucky and West Virginia, while failing to report suspicious orders to the DEA.

For example, from 2008 through 2011, the company distributed more than 3.7 million opioid pills to a pharmacy in Kermit, West Virginia, a town of 400 people in the southern part of the state, the indictment alleges.

Anthony Rattini, Miami-Luken’s president, and James Barclay, a compliance officer at the company, denied the allegations in court. Their attorneys declined to comment.

Miami-Luken’s attorney, Richard Blake, said the business is closed. In regard to the indictment, Blake said he is “waiting for information from the government to support its charges.”

The Plain Dealer analysis of the DEA database shows that Miami-Luken obtained two-thirds of the opioids it distributed to Temponeras from one of the nation’s largest drug manufacturers, Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals.

In 2017, Mallinckrodt paid $35 million to the U.S. Justice Department to settle claims involving oxycodone.

Distributors, such as Miami-Luken, provided Mallinckrodt with sales information to obtain discounts. In a release, the DEA stated that Mallinckrodt should have known about large and increasing orders from its distributors, and the company should have flagged individuals or other entities making those large purchases from the distributors.

The government alleged that from 2008 to 2011, “Mallinckrodt failed to design and implement an effective system to detect and report ‘suspicious orders’ for controlled substances — orders that are unusual in their frequency, size or other patterns” from 2008 to 2011, according to the DEA release.

The settlement was not an admission of liability.

There are no public records to suggest Mallinckrodt knew specifically about Temponeras. But from November 2008 to August 2010, Temponeras bought nearly 1 million opioid pills that were manufactured by Mallinckrodt’s subsidiary, SpecGx, and distributed by Miami-Luken.

In an email response, Mallinckrodt stated it “only sells products to DEA-registered distributors and other entities, not individual physicians, who are themselves registered with and monitored by the DEA.”

‘Vilified by the press’

Repeated attempts to reach Temponeras were unsuccessful. But in early 2011, The Plain Dealer wrote about the opioid issues in Scioto County and Appalachia. In the story, Temponeras complained that pain clinic doctors were treated unfairly.

“Some doctors are trying to help patients in a lot of pain,” Temponeras said. “We aren’t drug dealers, and we aren’t bad people. We are being vilified by the press and the fanatics who have had only negative experiences.”

Three months after the story appeared, more than 30 state and federal agents raided her offices, pulling files and searching patient records.

Temponeras called it “the worst day of my life,” according to court records. The raid, stemming from her large-scale ordering and prescribing of oxycodone, toppled her pain clinic and her practice. The DEA barred her from prescribing medication. In 2013, the State Medical Board permanently revoked her medical license.

Two years later, a federal grand jury indicted her, her father and Fankell, the pharmacist. All have pleaded guilty to drug conspiracy charges before U.S. Judge Timothy Black. Temponeras’ father and Fankell, 64, also have not been sentenced. All three are free on bond.

The State Medical Board revoked the license of John Temponeras. In 2011, the board cited his work at his daughter’s pain clinic. It also said he failed to keep inventory records on the handling of 27,500 dosage units of controlled substances in 2009 and 2010.

John Temponeras and Fankell each face minimal sentences of home detention or a few years in prison, according to court documents and interviews.

Defense attorney Brad Barbin said Margaret Temponeras took on a unique role of treating patients in chronic pain, people in need of a great deal of help.

He said in court documents that more than 70 patients wrote to officials that Temponeras “demonstrated exemplary professionalism and medical care.”

He said Temponeras took responsibility for what she did. He told the State Medical Board in 2013 that she did not desert her patients.

Grooms, Ira Marsh’s sister, isn’t so sure. Her brother left behind a wife, a son and three sisters.

“You could walk into her office and get whatever you wanted,” Grooms said. “He was defenseless. You have to have power to push away from drugs, and he didn’t have any. Once he found her, his addiction really took off.

“I would love to be in that courtroom when she is sentenced. Because I would tell that judge, ‘She killed my brother.’ “

HOW WE REPORTED THE STORY:

Figures in this story are derived primarily from a U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration database called the Automation of Reports and Consolidated Orders System, or ARCOS, which tracks the sale and shipment of controlled medications to pharmacies and doctors. A portion of the database covering 2006 to 2012 was released in July as the result of a judge’s order in U.S. District Court in Cleveland.

For The Plain Dealer’s analysis, the newspaper relied on a version of the data released by The Washington Post, one of the media companies that petitioned to have the data released. This analysis only includes oxycodone and hydrocodone, which constituted the bulk of prescription opioids sold in America from 2006 to 2012.

In addition, The Plain Dealer examined hundreds of pages of documents, including congressional testimony, state and federal court cases, records from the State Medical Board of Ohio and the Ohio Board of Pharmacy, as well as published reports and autopsy information.

ORIGINAL ARTICLE: https://www.cleveland.com/news/2019/09/unfathomable-how-16-million-pills-from-a-small-town-doctor-helped-fuel-the-opioid-crisis-in-ohio.html